22.3 One mean: Confidence intervals

We don’t know the value of μμ (the paremeter), the population mean, but we have an estimate: the value of ˉx¯x, the sample mean (the statistic). The actual value of μμ might be a bit larger than ˉx¯x, or a bit smaller than ˉx¯x; that is, μμ is probably about ˉx¯x, give-or-take a bit.

Furthermore, we have seen that the values of ˉx¯x vary from sample to sample (sampling variation), and noted that they vary with an approximate normal distribution. So, using the 68–95–99.7 rule, we could create an approximate 95% interval for the plausible values of μμ that may have given the observed values of the sample mean. This is a confidence interval.

A confidence interval (CI) for the population mean is an interval surrounding a sample mean. In general, an approximate 95% confidence interval (CI) for μμ is ˉx¯x give-or-take about two standard errors. In general, the confidence interval (CI) for μμ is

ˉx±Called the `margin of error'⏞(Multiplier×s.e.(ˉx)). For an approximate 95% CI, the multiplier is, as usual, about 2 (since about 95% of values are within two standard deviations of the mean from the 68–95–99.7 rule).

We often find 95% CIs, but we can find a CI with any level of confidence: we just need a different multiplier. We’ll just use a multiplier of 2 (and hence find approximate 95% CIs), and otherwise use software. Commonly, CIs are computed at 90%, 95% and 99% confidence levels.

If we collected many samples of a specific size, ˉx and s would be different for each sample, so the calculated CI would be different for each. Some CIs would straddle the population mean μ, and some would not; and we never know if the CI computed from our single sample straddles μ or not.

Loosely speaking, there is a 95% chance that our 95% CI straddles μ. For a CI computed from a single sample, we don’t know if our CI includes the value of μ or not. The CI could also be interpreted as the range of plausible values of μ that could have produced the observed value of ˉx.

Example 22.1 (School bags) A study of the school bags that 586 children (in Grades 6–8 in Tabriz, Iran) take to school found that the mean weight was ˉx=2.8 kg with a standard deviation of s=0.94 kg (Dianat et al. 2014).

The parameter is the population mean weight of school bags for Iranian children in Grades 6–8.

Of course, another sample of 586 children would produce a different sample mean: the sample mean varies from sample to sample.

The standard error of the sample mean is

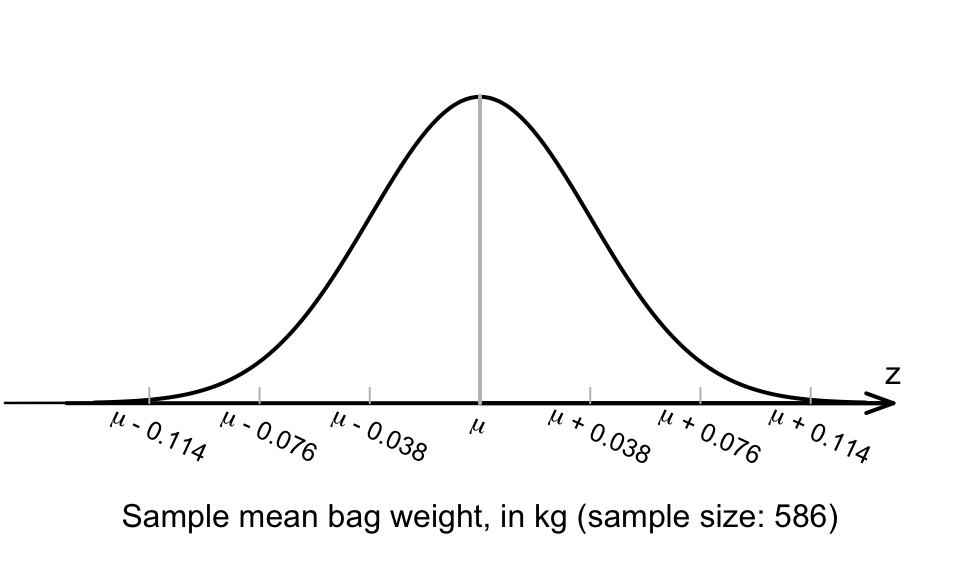

s.e.(ˉx)=s√n=0.94√586=0.03883; see Fig. 22.1. The approximate 95% CI for the population mean school-bag weight is

2.8±(2×0.03883), or 2.8±0.07766. (The margin of error is 0.07766.) This is equivalent to an approximate 95% CI from 2.72 kg to 2.88 kg. This CI has a 95% chance of straddling the population mean bag weight.

FIGURE 22.1: The normal distribution, showing how the sample mean bag weight varies in samples of size n=586