2.5 Two approaches to RQs

RQs can be approached in one of two ways:

- For estimation (confidence intervals): These RQs are concerned with, for example, estimating a value in a population. This value may be the size of a difference (probably a RQ with a Comparison), or strength of a relationship (probably a RQ with a Connection).

- For making decisions (hypothesis testing): These RQs are concerned with making a decision about an unknown population value: for example, is the percentage the same in two different groups of the population?

Think 2.7 (RQ type) What approach do these RQs take: Decision-making, or Estimation?

- Among Australian upper-limb amputees, is the percentage wearing prosthesis ‘all the time’ the same for transradial and transhumeral amputations? (Davidson 2002)

- In New York, what is the difference between the average height of oaks trees (ten weeks after planting) comparing trees planted in a concrete sidewalk and a grassed sidewalk? (Grabosky and Bassuk 2016)

- What is the average response time of paramedics to emergency calls? (Pons et al. 2005)

- Is there a relationship between the average weekly hours of physical activity in children and the weekly maximum temperature? (Edwards et al. 2015)

2.5.1 Estimation: Confidence intervals questions

![]()

Sometimes, the RQ concerns how precisely a value in the population is estimated by the sample. This value may measure a difference, or the strength of a relationship.

These RQs are studied in Chapters 19 to 25, and in Sect. 35.7.

Example 2.17 (Estimation RQs) Consider this RQ (based on Barrett et al. (2010)):

Among Australian teens with a common cold, how much shorter are cold symptoms, on average, for teens taking a daily dose of echinacea compared to teens taking no medication?

This RQ asks about size of the difference (in the population) between the average duration of cold symptoms.

Only sample data are available, and there may be no difference (on average) at all in the population.2.5.2 Making decisions: Hypothesis testing questions

![]()

Sometimes, RQs are not about the precision with which a population value is estimated by the sample, but instead about deciding if a difference or a relationship exists in the population.

These RQs often are associated with hypotheses: statements that suggest possible answers to the RQ. Based on the sample, the hypothesis best supported by the data is to be chosen.

These RQs are studied in Chapters 26 to 31, and in Sect. 35.6.

Example 2.18 (Making decisions with samples) Consider this RQ (based on Barrett et al. (2010)):

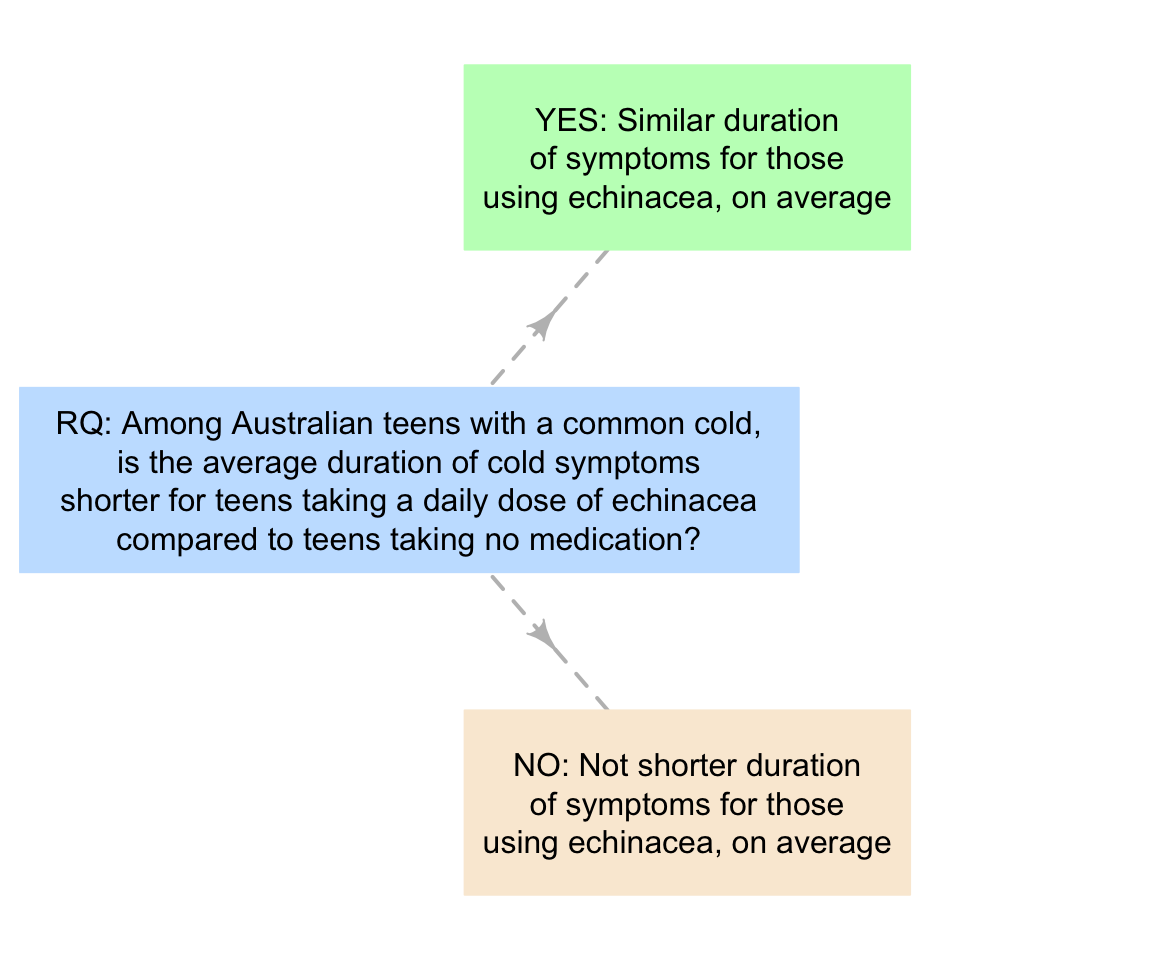

Among Australian teens with a common cold, is the average duration of cold symptoms shorter for teens taking a daily dose of echinacea compared to teens taking no medication?

This is a decision-type RQ, with two possible answers (Fig. 2.3): Either echinacea does result in shorter average cold durations, or it doesn’t. In practice the answer is rarely clear cut, and instead how much evidence there is in the sample to support a particular hypothesis about the population is reported.

Evidence may support or to contradict a hypothesis; evidence rarely proves a hypothesis (at least, without any other support, such as theortical support). Ultimately, after collecting data from a sample, a decision must be made about which explanation about the population is more consistent with the data collected.

FIGURE 2.3: Two possible answers to the RQ about echinacea